| AN INTERVIEW WITH OLIVER POSTGATE |

|

|

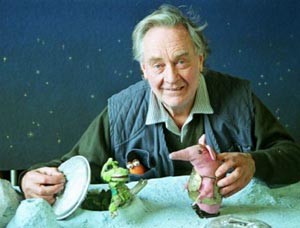

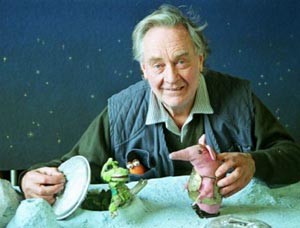

A few years ago, I was lucky enough to have the chance to talk to Oliver Postgate, creator of The Clangers, Ivor the Engine, Bagpuss and Noggin the Nog, about his work making some of the most popular and well-loved children's programmes of all time.

(Update: on 8th October 2008, Oliver Postgate died at the grand age of 83. His contribution to British television was both legendary and brilliant, and he’ll be sadly missed. I would therefore like to respectfully dedicate this article to his memory.)

Clive Banks: Hi Oliver, it’s nice to talk to you. Let’s start with how you first got into television.

Oliver Postgate: I got into television in 1957, as a stage manager at Associated Rediffusion which had a London franchise, and I was given over as a sort of tea boy to the children’s programmes, which were a poor relation of proper programmes and had budgets of about a hundred pounds or so for each five or ten minute programme which even then wasn’t a lot of money. And I looked at some of the stuff they were putting out which were sort of black and white Jackanory sort of things, and I thought I could do better than that if I had to, so I wrote something called Alexander the Mouse, about a mouse born to be king; and at the same time, Associated Rediffusion got a mad Irishman who turned up with a magnetic animation system, by which you could move characters about on a flat surface by putting a magnet under the table, and have a forty-five degree mirror on top. This was very suitable for Alexander the Mouse, he being a mouse who slid along with a magnet, so we did about twenty-six of these I think altogether, and I managed to get Peter Firmin to make the backgrounds and mice and things for the stories each week. We got thirty quid a week each for me to do the stories and tell them live on television, and he to make these things, but it was a complete bloody nightmare because the mouse had a magnet on its underside, and you had to approach it with a magnet in the hope that you would hit it where it was, otherwise it went scootling across the picture to where the magnet was, or alternatively turned itself upside down, or worse than that if you happened to put it exactly right but with the polarity the wrong way round, the flat cardboard mouse would leap into the air and turn itself onto its back and come down again showing its Sellotape, and all you could do was reach a hand into the picture and turn it the right way up! So that was the situation and it drove us completely mad. So I went in to the head of department and said I wanted to make the next lot on film, but he said there wasn’t enough money in the budget; I said “How much is there?” and he said “A hundred-and seventy-five pounds a show”, so I said “Alright, I’ll make them for that”. I went away and made an animation table in my bedroom and got Peter to do the figures and did it in single-frame 16mm animation pushing the characters about with a pin and pressing a button, which was rather laborious. [This was] called The Journey of Master Ho, and that was intended for deaf children; it had the great advantage that it had no soundtrack. It was a Chinese story, and I knew a young man who was an honorary Chinese painter, and he would do the backgrounds for me. But he didn’t understand that flat animation under a camera had to move dead sideways in the Egyptian manner, not in the Chinese manner of seeing thing in three-quarters view, so that when I had to move them flat across the background they all looked as if they had one short leg! But it seemed to work alright, and it was tremendously exciting as a job and I enjoyed it enormously.”

CB: Where did the inspiration for Ivor the Engine come from?

OP: I was in drama school in 1948, when I was twenty-three and had just come back from the wars – not that I was in the wars, I was in Germany with the Red Cross – and there was Denzyl Ellis, who used to be the fireman on the Royal Scot. It was his job to get up in the morning to put new fire bars in and light the engine with newspaper and selected pieces of wood and coal, just like you would with a boiler, at three o’clock in the morning, so that by the time it was ready to leave from Paddington it was boiling and ready to go. He always said it gave a sort of human quality to the idea of this great hundred-ton monster hurtling up to Scotland with him shovelling coal into it, and there ought to be a story there, and I thought that there ought to be a story there as well, so when Associated Rediffusion wanted a new story to follow after Alexander and Master Ho I talked to Peter [about it.] I was intoxicated by the work of Dylan Thomas, and used to carry ‘Under Milk Wood’ round in my pocket… Wales is where you have little railways going along the tops of hills, which is much less boring that hurtling up the slumbering Midlands plain in the middle of the night, so we decided it would be nice to set it in Wales, so Ivor the Engine is entirely bogus as far as Wales is concerned - it’s built entirely on a picture of Wales given by Dylan Thomas! Then, literally in the bath, I came to realise what the story was: the engine wanted to sing in the choir, which is obviously what a Welsh engine would want, so from then on it fell into place. [This] indicates the way we worked, in that we didn’t use magic or science-fiction in the extraordinary sense, we simply altered one parameter of ordinary life, and the people of the district treated this as being perfectly ordinary, so they went to a great deal of trouble to get Ivor his whistles and the organ pipes from Morgan the Roundabout. I thought that was the end of the story but ITV just immediately ordered thirteen more, so we had to think of other things to happen: dragons, and various other unlikely characters turned up. Ivor was made first of all in black and white, and then in 1975 when I’d run out of ideas, Monica Simms at the BBC said “What we’ve always wanted is Ivor’”, so I said “Shall I make them again?” and they said “Oh, yes please!”. So I then made the second lot, forty of those in colour, and they’re certainly much better than the originals.”

CB: And you narrated the show as well.

OP: Well, I’d written it so I might as well tell it! I mean we hadn’t got any money – the first lot I did all the voices myself, because the amount they were paying for them was such peanuts that I had no alternative.

CB: This was all made in Peter Firmin’s infamous cowshed?

OP: Oh yes! I was there with the sweat running down my hands – I sat in that bloody shed for months on end sometimes! But it was very, very absorbing work, you have to concentrate very hard, and you can lose yourself in a day’s work very easily and not notice it. The lovely thing is that because I filmed exactly to the soundtrack, which I had already numbered in film frames, it meant that I didn’t have any editing to do. So that when the rushes came back from the labs I just laced them up with the soundtrack, which was on a separate film, and we saw them with the sound on immediately. So everybody came into the studio once I’d go the rushes back and we saw the work we had done in the last week come to life, and that was exciting! I really enjoyed that!

CB: How long did it take to make an episode?

OP: Well, let me see, five minutes, that’s two reels, I think that would have taken me inside of a week. Mind you, the preparation was much longer, as I had to do the soundtracks first because Peter would get his pictures of the people from listening to them talking. It was me and Olwen Griffiths, who’s Welsh, and Tony Jackson, who is a very good actor and a great friend; [Tony] and I shared the male parts and Olwyn the female ones. I also had to get the music from Vernon Elliott and have a recording session with him and members of the Philharmonia [Orchestra]… and I’d have to cut all these together in the basement of my house; then Peter and I would sit and play it over and over again on cassette to work out the lengths of the pictures we wanted. He would then paint the backgrounds and give me loads of tins of arms and legs; the great invention that made all this possible was Blu-Tac because you can make a little ball of it and stick somebody’s arm or head on with it, then, at a moment of drama in the story, you could rip it off and put on a new one that was fraught with alarm. A little ball of Blu-Tak for an arm joint doesn’t wobble about, doesn’t wander, and will stay where you left it.

CB: A trade secret revealed!

OP: Yes! The man who recently tried to remake Ivor the Engine with a computer for BBC Wales - who had adopted it as their mascot, even though I told quite straight out that he was completely bogus Welsh - got an expert with a computer to imitate my way of working. And he said: “that’ll be a doddle” – but it wasn’t! He found that it took him five times as long to do anything, when all I did was push it along with a pin and push a button.

CB: Lots of programmes are now being remade: Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and now Doctor Who. Would you consider remaking any of your old shows?

OP: It depends – I don’t want anybody to remake mine particularly, except the recent BBC Wales promotional film of Ivor, because I think they are what they are. Two or three times in the last five or six years big companies have come to us to remake Noggin the Nog in particular, but they each had to make a pilot which might cost them up to five or six hundred thousand pounds. So they went all round the world to different TV stations to try and get subscriptions, but for each country they went to, each one wanted it altered to suit their largest-paying audience, so any nuances of fun which we left in got taken out because they mightn’t understand them. When it came back, The Saga of Noggin the Nog was totally changed, all the stories had to be turned round so that it was about Noggin’s son instead, it had to have more violence in it… it was complete rubbish and I told them to get stuffed! Aardman wanted to do it once, and I would have been happy for them to do it in plasticene because that wouldn’t have been in any sort of conflict in ours, but they worked out they couldn’t afford it and it wouldn’t give enough return. We went down to their studio as their guests to look at what they had there, and the equipment there was absolutely astonishingly marvellous; but everything was so expensive, and they were getting two-and-a-half seconds a day out, and I said well, I used to have to get a hundred-and-twenty seconds a day in order to eat! They thought they could find a way of making ‘Noggin’ films, but eventually concluded that to make anything by their method would cost too much. Nick Park said that Ivor the Engine was the thing that set him off into animation, that I was his inspiration, which was very kind of him to say that.

CB: The next thing you did was Pingwings, and then The Pogles, which I understand was seen as too frightening by the BBC.

OP: Yes, the first Pogles was a single one I made intending to do a series, but, quite rightly, the BBC said it was too frightening cos the witch was a proper witch, and they said witches are alright in fairyland and places like that, but not in the back garden. I must say, I read the witch really rather well. It was a very frightening story, but I love it, it was great! Then the BBC said “This won’t do, do us some Watch With Mothers about the Pogles, but keep the magic quite tidy, like the magic plant”, so I made two lots of twenty-six in black and white. Some of the best stuff we ever did was in those.

CB: Let’s move onto The Clangers. Where did the idea for these woolly creatures come from?

OP: The Clangers themselves actually originated in a Noggin First Reader. The Noggin stories were published by Kay and Ward, and are much sought-after little books of the actual Noggin sagas; they also published some ‘learning to read’ books, which were short Noggin stories, and one was called Noggin and the Moonmouse, and it concerned a new horse-trough that was put up in the middle of the town in the North-Lands. A spacecraft hurtled down and splashed into it, and the top unscrewed and out came a largish, mouse-like character in a duffel coat, who wanted fuel for his spacecraft. Eventually, he showed Nooka and the children that what he needed was vinegar and soap-flakes… so they filled up the various tanks up in this little spherical ship and took off in a dreadful cloud smelling of vinegar and soap-flakes, covering the town with bubbles! When the BBC told us in 1969 that we had to go into colour, which I’d never used, and it had to be “new and marvellous, and a lot better than the last thing you did, darling”, but they no idea about what they wanted. In 1969 space was the place to look, so we got out our virtual telescopes and had a look round to see if the Moonmouse was still about, and there he was – he’d lost his tail because it kept getting into the soup, and wore armour against the space debris that kept falling onto the planet lost from other places, like television sets and bits of an Iron Chicken.

CB: And they got a lot bigger too, didn’t they? Most people think the Clangers are tiny, but in a couple of episodes we see that they are the same size as a human astronaut.

OP: Yes, that’s right! The only reason they got bigger was so that Peter could use an Action Man as the armature for his spaceman. If not, you’d just have seen the Spaceman’s feet on the Clangers’ planet, so they grew to about four-foot high.

CB: I heard a rumour that the Clangers swore! Is this an urban myth, or is it true?

OP: Yes, absolutely! Their scripts had to be written out in English, for Steven Sylvester and I to use Swanny whistles; we just sort of blew the whistles in Clanger language for the text that was there, so it didn’t matter much what was written. But when the BBC got the script, [they] rang me up and said “At the beginning of episode three, where the doors get stuck, Major Clanger says 'sod it, the bloody thing’s stuck again'. Well, darling, you can’t say that on Children’s television, you know, I mean you just can’t.” I said “It’s not going to be said, it’s going to be whistled”, but [they] just said “But people will know!” I said no, that if they had nice minds, they’d think “Oh dear, the silly thing’s not working properly”. If you watch the episode, the one where the rocket goes up and shoots down the Iron Chicken, Major Clanger kicks the door to make it work and his first words are “Sod it, the bloody thing’s stuck again”. Years later, when the merchandising took off, the Golden Bear company wanted a Clanger and a Clanger phrase for it to make when you squeezed it, they got “Sod it, the bloody thing’s stuck again”!

CB: Now that’s funny, cos I’ve got one on my shelf and never realised that’s what it was saying!

OP: Yes - my tax inspector’s got one, but he says that it doesn’t say that, it says “Sod it, I’ve got the bloody sum’s wrong again!”

CB: There’s one episode called Vote For Froglet, which I’ve never seen.

OP: And you won’t! It doesn’t exist [any more]. I was so angry in 1973, the Winter of Discontent, when the Miners Union and the government were locked in mortal combat and the economy of the country was going into the ground, that I honestly thought, having been in Germany at the end of the War and seen what happened when an economy collapsed completely, I really got frightened, I thought the process of government was completely buggered by inter-party squabbling. So I went to the BBC and said, “Can I do a little Clangers film about the election?” It’s basically about the narrator, that’s me, being the interlocutor as well, telling the Clangers that they’ve got to vote, either for the Froglet or for the Soup Dragon. And they refused point blank to have anything to do with it. It was a sort of tiny morality play really. It only lasted three to four minutes and I made it complete in three days.

CB: So who won the election?

OP: Nobody did! They all went back down to their holes and said “Sod off! The whole thing is a waste of everybody’s time!” I was trying to sell them the idea of politics, and they were determined not to have anything to do with it.

CB: It’s very interesting that you were trying to break the ‘Fourth Wall’ on that one.

OP: Yes. I wasn’t sure if it would work but it did. I was in conversation with the Clangers and they were answering me back. But it was only done just the once for that purpose, and it wasn’t shown during Children’s television time. It was shown three or four times and got a good laugh, but it had no effect on the Election. I don’t know whether it’s completely lost, we did find the rusty tin once, but nobody has asked for it to be resuscitated. Well, actually there might be with this Election [2005] if everything gets too silly.

CB: It was also nice to see the Clangers in Doctor Who, as the Master watched it on television in his prison cell and thought they were real!

OP: Yes, that’s right! I remember that one! That was a great sort of accolade, at the time people said, “Those are the things in Doctor Who”, because ten million more people saw them in Doctor Who than had ever seen them on the Children’s [broadcast].

CB: Moving onto Bagpuss. How did the idea behind that programme come about?

OP: Bagpuss is Peter’s basically. He had in his head in an Indian Army cat in a children’s hospital in Poonah, and it had this faculty that when it told stories to the children there, the stories magically appeared above its head. We both thought this was a good idea for television, but I said I’m buggered if I’m going to have a load of children in the cowshed.” I can deal with puppets, but not with children – not with puppets that answer back! So we put him in a shop window. Madeleine was a rag doll which Joan Firmin made for Katy when she was a girl, and the toad, Gabriel, was a character which had played with Rolf Harris and Peter in a programme called Musical Box, and he had the great advantage of having mechanics inside him, so that when he came to singing songs, I could run the camera at full speed and Peter could animate it to the song, which is a hell of a lot easier than trying to [do] songs in single frames, because they’re terribly difficult to catch the beat. The only one we had trouble with was Professor Yaffle, because Peter [originally] thought of ‘Professor Bogwood’, who was a rather drab, very dark character, very sort of nondescript, too nondescript actually, he was so dull. And I remembered a philosopher [I met] when I was young, Bertrand Russell, I remembered him as being [does the voice] very, very dry with a very thin voice; and there was also my Uncle Douglas, G.D.H. Cole, who was Professor of Economic History at the University of Oxford, and he also had this very dry voice and no sense of humour. So I got the voice first of all, it was a sort of “nyup-nyup-nyup-nyup”, and Peter said “It’s some sort of bird, yes, it’s a yaffle, a woodpecker bird.” And he knew everything. We just threw the mice in loose, they didn’t come from anywhere, and they took the mickey the whole time, which was great cos we could never take the mickey from our uncle Douglas because he had no sense of humour, and poor Yaffle had to put up with it.

CB: And Bagpuss was supposed to be marmalade originally?

OP: Yes, that’s right. The people who were making the material for Peter said “We’ve had a terrible accident with the vat, and we thought we’d better show it to you, but it’s terrible, it’s all wrong,” and they took out this cream and shocking pink striped material and held it up, and Peter and Joan stood there in the yard looking at it – I remember them to this day standing there and looking at it – and they said “What the gods have sent us, we shall have”, and they took it and accepted it and thought “It’s not going to be a marmalade cat, it’s going to be the cat it was”, and we’ve never regretted it!

CB: And a legend was born!

OP: That’s right! Pure chance!

CB: I understand that Bagpuss accompanied you to the University of Kent to receive a Master of Arts award.

OP: Peter and I were given honorary M.A.s by the University of Kent at Canterbury, on condition that Bagpuss came along, robed, with mortarboard and gown, and share the award with us. They said they couldn’t actually award him a degree because he was a fiction, and the charter of the University didn’t allow them to give honorary degrees to fictions. The only reason they gave us honorary MAs was because of Bagpuss, and so we took Bagpuss along, and I made a speech on Bagpuss’ behalf, in which he let them know that he had no truck with this bourgeois flummery [because] he was an Orthodox Miaoist, which got a good laugh from the university people and caused the cathedral authorities considerable embarrassment at the time because it was taking place in Canterbury Cathedral and they didn’t care for ribald laughter filling the place!

CB: What’s happened to Bagpuss since?

OP: In 1987 the BBC decided that Bagpuss was too old-fashioned to be shown, but then in 1999 it got the award for being the best children’s film ever, and suddenly the merchandising took off, which has been great, it’s like a pension for me now. Bagpuss has actually bought a children’s hospice in Romania, which he’s rather pleased about. He earned our living in 1974 and 1987 - very nicely thank you - and then suddenly to come back and get all this merchandising money, well, Peter and I said “It doesn’t belong to us, it belongs to the cat”, so we consulted – hypothetically – with the cat, and decided to open this hospice. We managed to build the whole hospice for about a hundred-thousand quid, which would have been at least a million in this country, so the cat was very pleased that he’d been properly provident with his money!

CB: What happened after you’d finished on Bagpuss?

OP: Well, the muse went after that. She said “I’ve made you twelve complete worlds down to the last nut and bolt, helmet and flipper, and that’s your lot.” So I made some films based on a Rumer Godden story, The Doll’s House, which was quite fun to make, and quite nice to do but it was not of my origination, which was really in a sense a great comfort. Rumer had no sense of making films, so she would set things on the tops of buses, which you couldn’t do, but we managed to make a nice set of films. Then I made a film for the United Nations about nuclear disarmament, which was a particular passion of mine at the time. I made some films which Peter wrote called Pinny’s House, and by then it was 1986, my family had all vanished and I thought “Bugger it, I’m not going to sit in that drafty shed for six months at a time, thank you”, and I went back to the Twelfth Century and painted a fifty-six foot long Bayeux Tapestry thing of the story of the life and death of Thomas Becket. I made a film of that, a storyboard film as a sequence of stills, which was shown, and sold videos of, in Canterbury Museum for years. I’m now engaged in remaking that on the computer because they’re going to reshow the Illumination as it’s called in Canterbury Museum, and they’re going to sell DVDs of this which I’m going to make. It’s come round full circle to where I was sixteen years ago.

CB: Oliver, thank you very much.

Interview conducted by Clive Banks, March 2005

The Complete Ivor the Engine, The Clangers - Series 1 and The Complete Bagpuss are available on DVD from by U.C.A. (Universal Pictures (UK) Ltd. and Columbia Tri-Star Home Entertainment Alliance)

Oliver Postgate’s autobiography, ‘Seeing Things’ is published by Pan-MacMillan

|

You can buy merchandise of Oliver's shows, and other classic children's television series, at:

|

www.oliverpostgate.co.uk

Oliver’s personal website, for some of his personal opinions and self-confessed rants, with interruptions by Bagpuss

www.catchat.org

Bagpuss is patron of this organisation, which finds homes for homeless cats (a kind of ‘Meow-Bay’)

www.smallfilms.co.uk

The official Smallfilms Treasury website

www.dragons-friendly-society.co.uk

For all things on The Saga of Noggin the Nog, Pogles' Wood and Pingwings

Back to the Clangers Intro Page

Back to the Databanks Main Page

where you'll find guides to some of the best cult and classic science fiction and telefantasy programmes ever transmitted!